Distance Learning Module 4 - Afghanistan Lakes

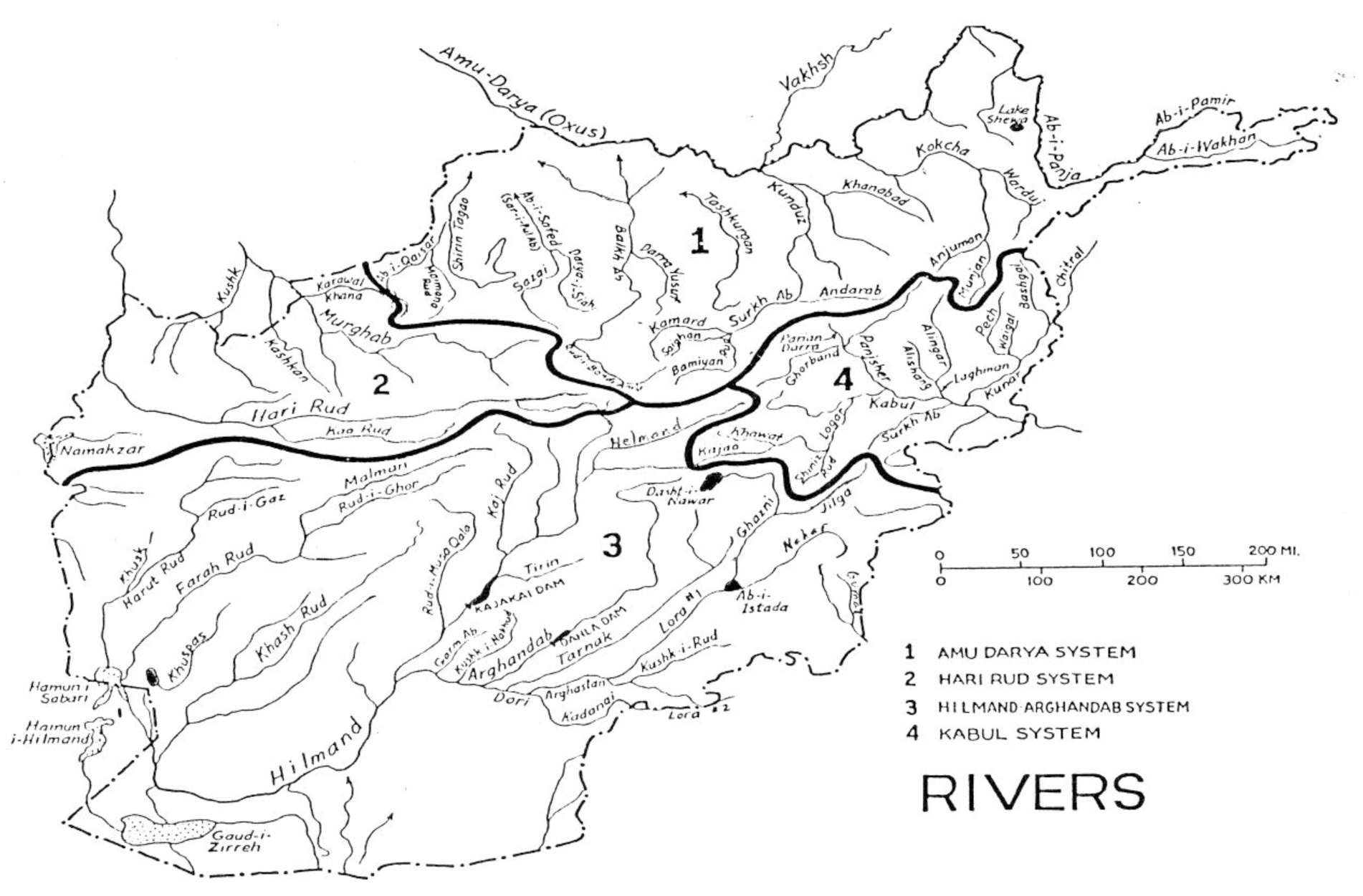

Lakes in Afghanistan are not common in most parts but are most important for providing water for people, animals, and for providing freshwater recharge that soaks down into the underground aquifers where tube wells and karez irrigation can be used to get the good water (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Map of Afghanistan showing some of the larger lakes (Lake Shewa, Dashti Nawar, Abi Istada, Hamuni Saberi, Hamuni Hilmand, Gaudi Zirreh, Abi Istada).

- Lakes can be mostly freshwater in the mountains and northeast of Afghanistan (Figure 4.2 & 4.3).

Figure 4.2. Glacial lake in the Wakhan Corridor where the ancient ice melted away and left behind a lake in the rock basin that was eroded by the ice originally.

Figure 4.3. Lake Chaqmaqtin Kol, high in the Wakhan Corridor and from where the Abi Wakhan once came but now flows out to the north though the Aq Su around through the Tajikistan Pamir to join the Panj lower down. This lake was formed in the giant rock basin carved by the ice where the ice was once very thick here before it melted away a few thousand years ago. Lake Zori Kol, which is the source of the Abi Pamir tributary to the Panj, is also such a glacier basin lake in the Wakhan Corridor.

- Lakes in the lowlands of southern southwestern, western, northwester and north Afghanistan are commonly salt and not useful for drinking water, but some of the different salts can be very useful and can be sold for much money (Figure 4.4A&B; 4.5A&B).

Figure 4.4A. Satellite picture of Namaksar Andkhoy wilh scale bar in the lower left that is 1 km long.

Figure 4.4B. Picture taken on the ground showing Namaksar Andkhoy, which is a basin blown out by strong winds from the northwest. Sometimes it has water in it briefly before it drys out to leave behind the white salt.

Figure 4.5A. Namaksar Herat is a dry salt lake on the border with Iran that was produced millions of years ago by down faulting where the rock mountains around it broke and moved downward. The scale bar in the upper middle is 5 km long. The yellow line running up and down on the left marks the international border with Iran.

Figure 4.5B. Lake Abi Istada is a place along the famous Chaman – Quetta Fault that the fault has caused to be pulled down. This lake has been drying up in recent years, which it did not used to do.

-

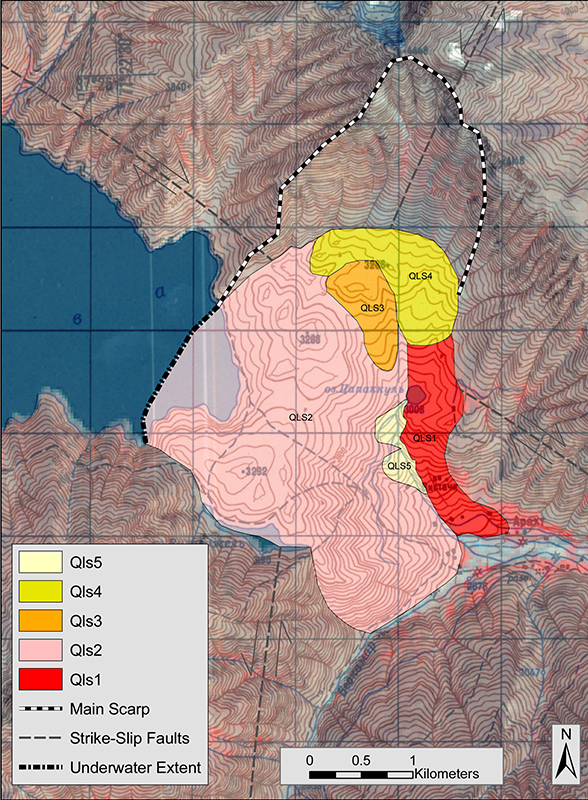

Lakes are formed by many quite different processes – glaciers, rivers, , wind blowouts, landslides, natural carbonate buildups, tectonics (downwarping, faulting), volcanos, and the hand of man. A big landslide dam in the Badakshan Pamir of Afghanistan is Lake Shewa (Figure 4.6). Lake Shewa was probably caused by earthquakes where two crossing strike-slip faults have broken up the rocks as they moved and the mountain fell down from the north.

Figure 4.6 Map of the dam of Lake Shewa that was put in place thousands of years ago, probably by earthquakes on the strike-slip faults that cross underneath it. Landslides Qls1 and Qls2 where the first slope failures there, followed Qls3 and Qls4 later. The lake on the left was filled up by river that flowed in from the left (west) and then on out the right (east) into the Panj which flows by a few km away.

- The famous lakes of Bandi Amir (Figure 4.7) have dammed themselves (self-damming) by the special buildup of travertine rock (CaCO3, or calcium carbonate), which comes out of the water where it is too cold.

Figure 4.7. Bandi Amir.

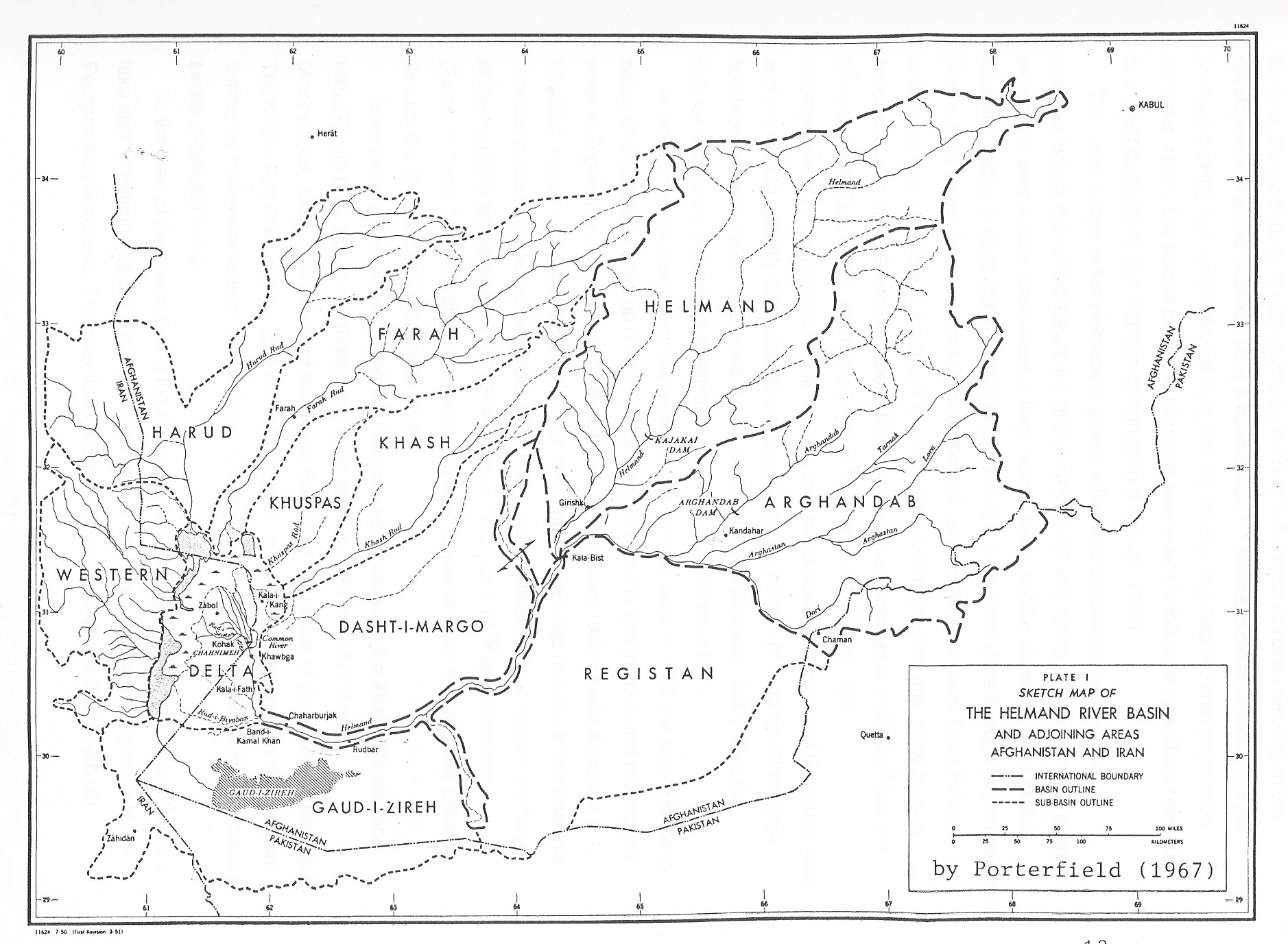

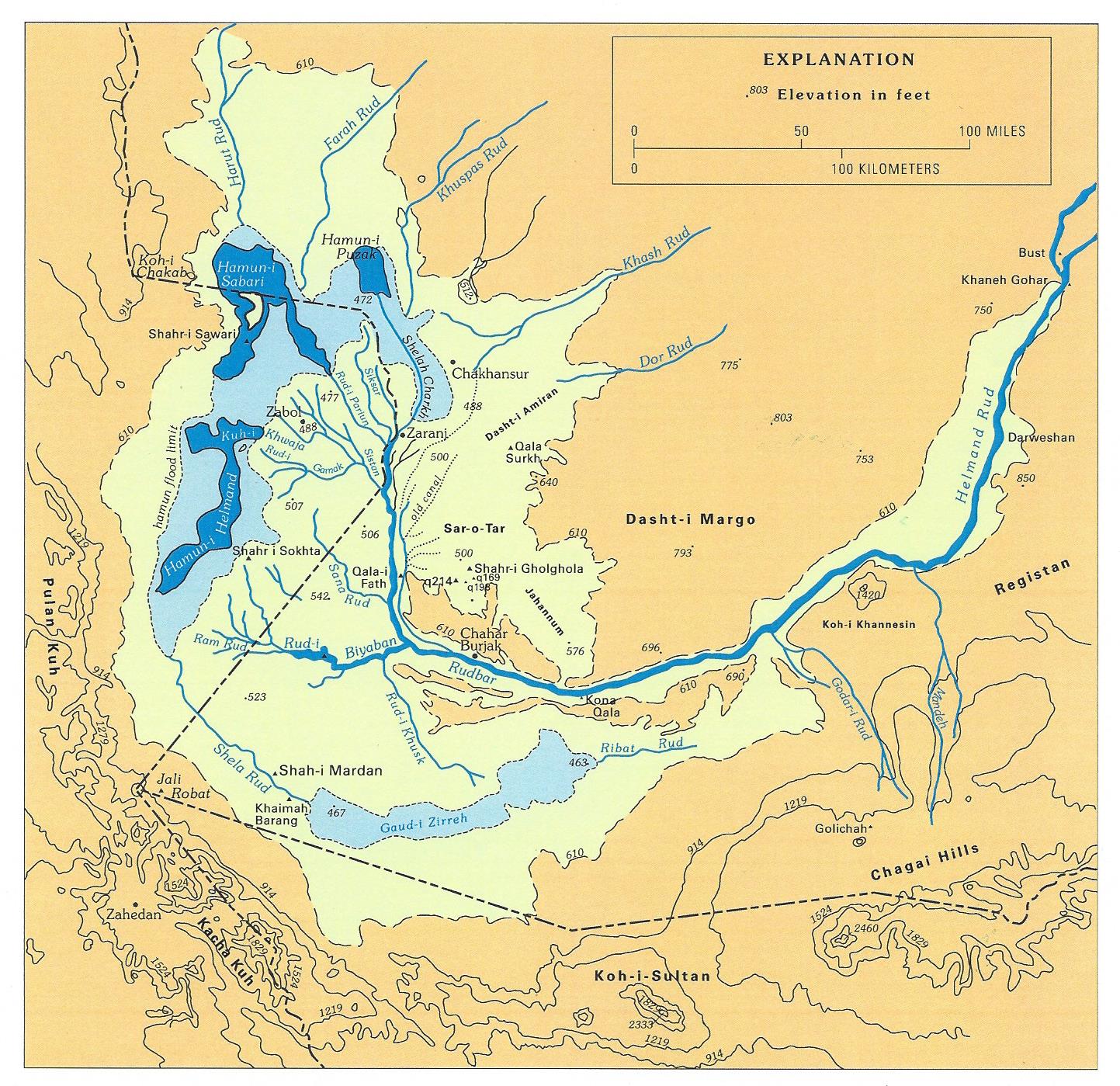

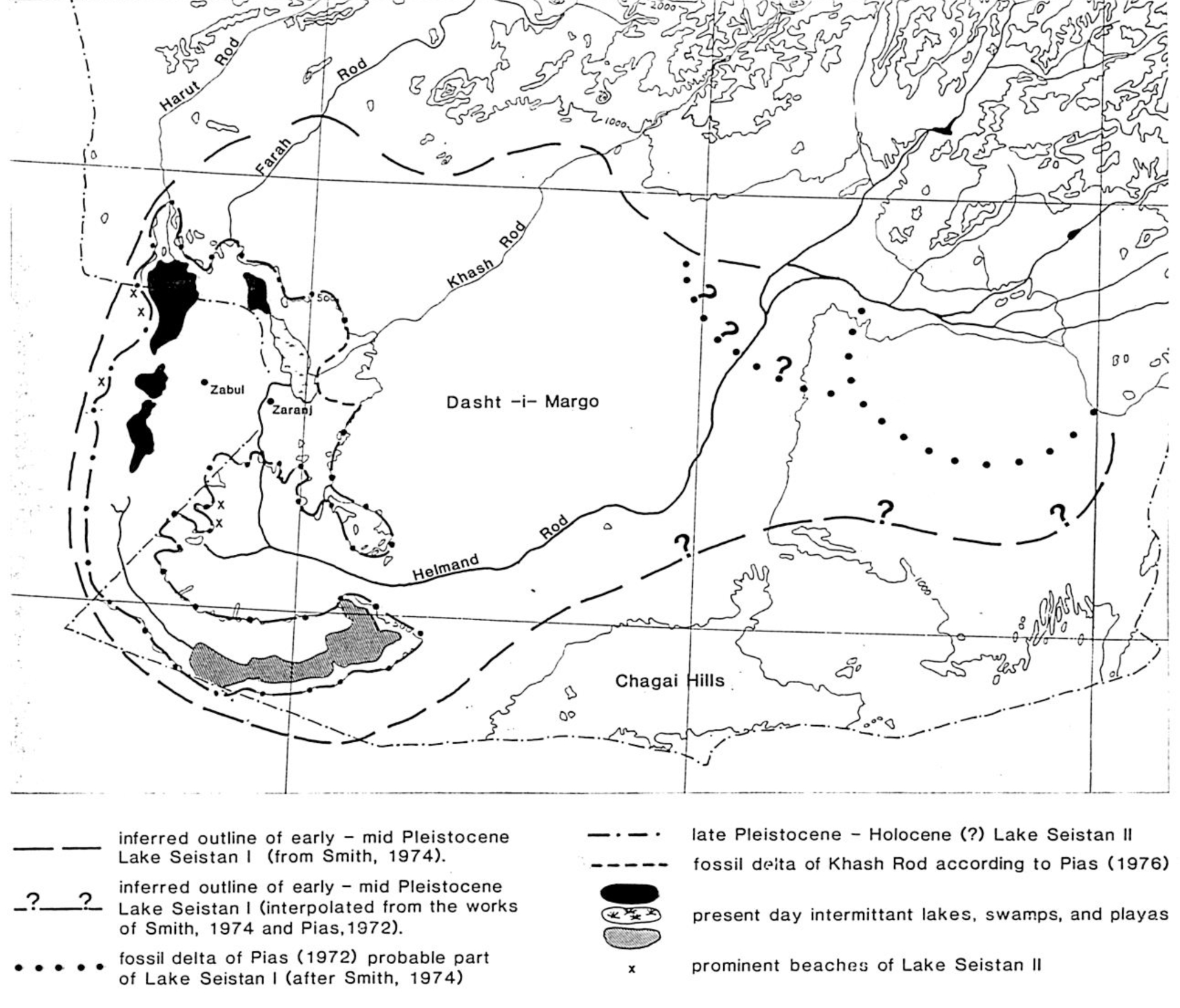

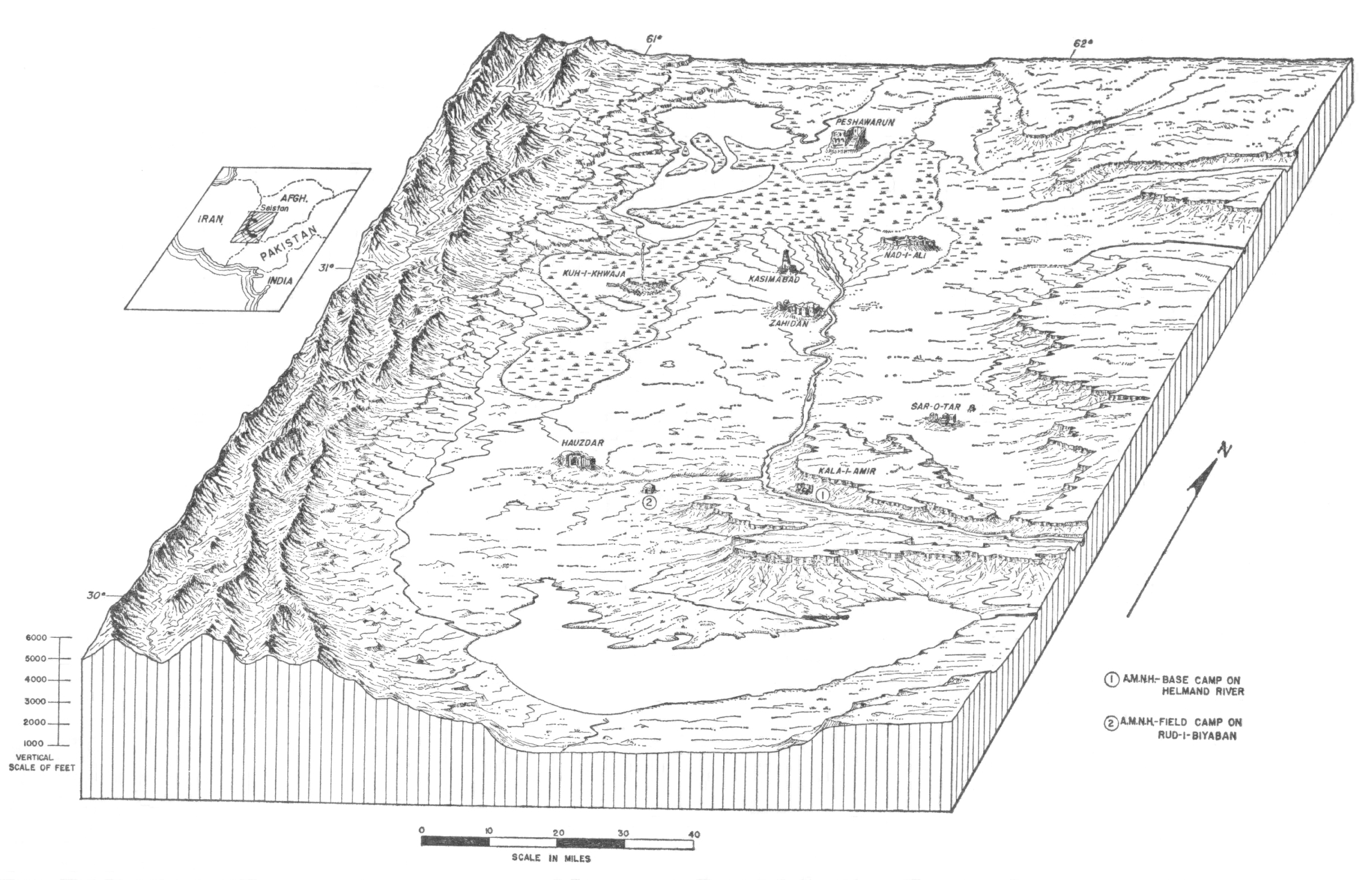

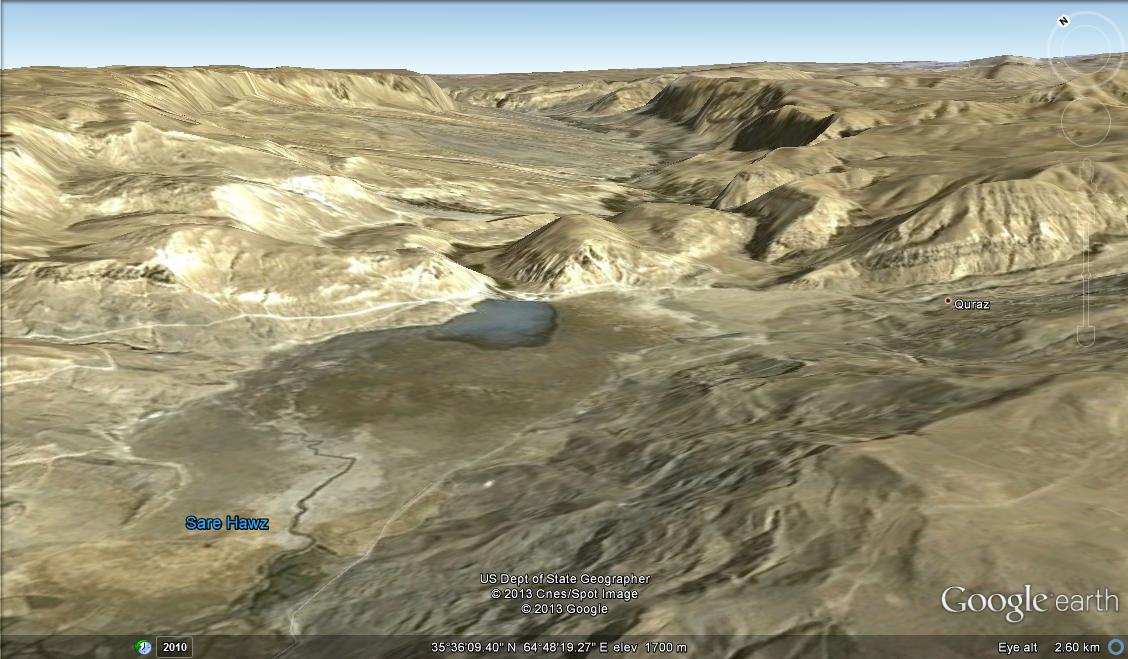

- Some lakes form where the ground has been pulled down by fault movements (Figure 4.7A&B; 4.8A&B), such as the whole Seistan Basin depression into which the Helmand River sends its waters, or the little Sari Howz lake near Maimana in the northwest of Afghanistan fault movements have blocked one of the rivers there (Figure 4.9).

Figure 4.7A. Some lakes in Afghanistan fill up after the winter snowmelt and then dry out in the hot summer and high winds (badi sado bist roz).

Figure 4.7B Map of the lower Helmand River where the winter snowmelt from the Hindu Kush finally flows into the intermittent hamoun lakes on the border with Iran.

Figure 4.8A. Map of the large basin of the Seistan in Southwest Afghanistan. Many thousand years ago, much bigger lakes existed here that were filled by a one much larger Helmand River, but have been shrinking ever since.

Figure 4.8B Drawing of the Helmand Delta area in the bottom of the Seistan Basin where the lakes have been drying up. The dry lake of Gaudi Zirreh is the larger white expanse in the bottom center of the picture.

Figure 4.9. Satellite picture of the Sari Howz area looking off northeast where a fault has brought rocks up across to dam the river.

- Lakes form inside volcanos all over the world where the mountain top explodes outward and then drops down or subsides (Figure 4.10). Dashti Nawar, near Ghazni is the remains of an extinct volcano that last exploded about 2.2 million years ago, leaving behind a giant basin.

Figure 4.10. Satellite picture of Dashti Nawar from an altitude of about 47 km above. The scale bar at the top is 5 km long.

- Some lakes in Afghanistan have formed as basins that collect water for unknown reasons.

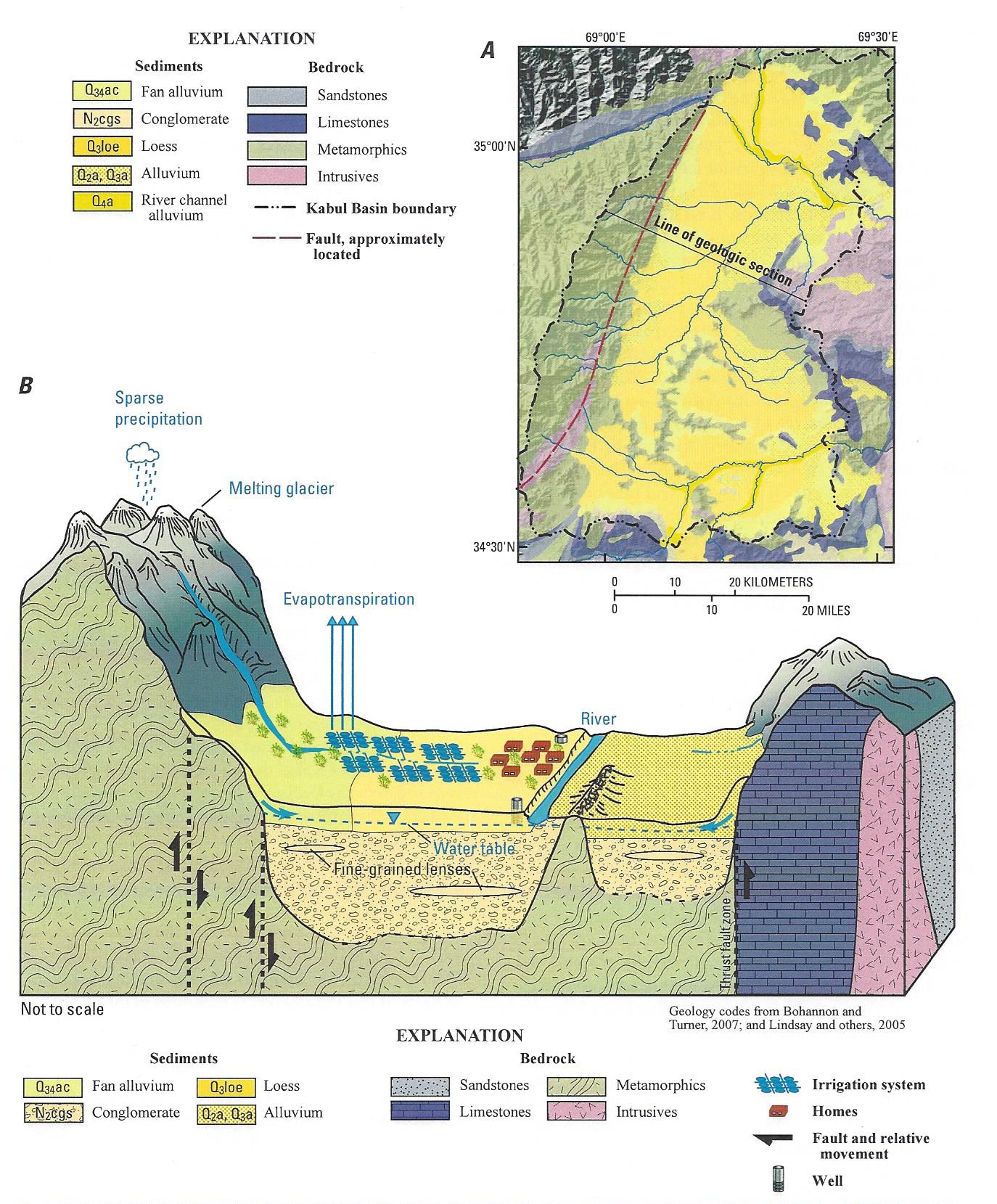

- Lake Hashmat Khan, for example, formed for complicated reasons on the outskirts of Kabul City, but it now serves as a most important place where surface water soaks or infiltrates underground to replenish the ground-water level from where it is been pumped down by wells (figures 4.11 & 4.12).

Figure 4.11. Airplane picture of lake in southern Kabul called Hashmat Khan (Shuhada Salaheen), looking to the southeast in winter when it was full of water.

Figure 4.12. Upper map and lower drawing of the Kabul Basin underground to show the water table that has been pumped down under the city, but which can be refilled by recharge from places where rivers or lakes can infiltrate through the sediment downward.