Featured

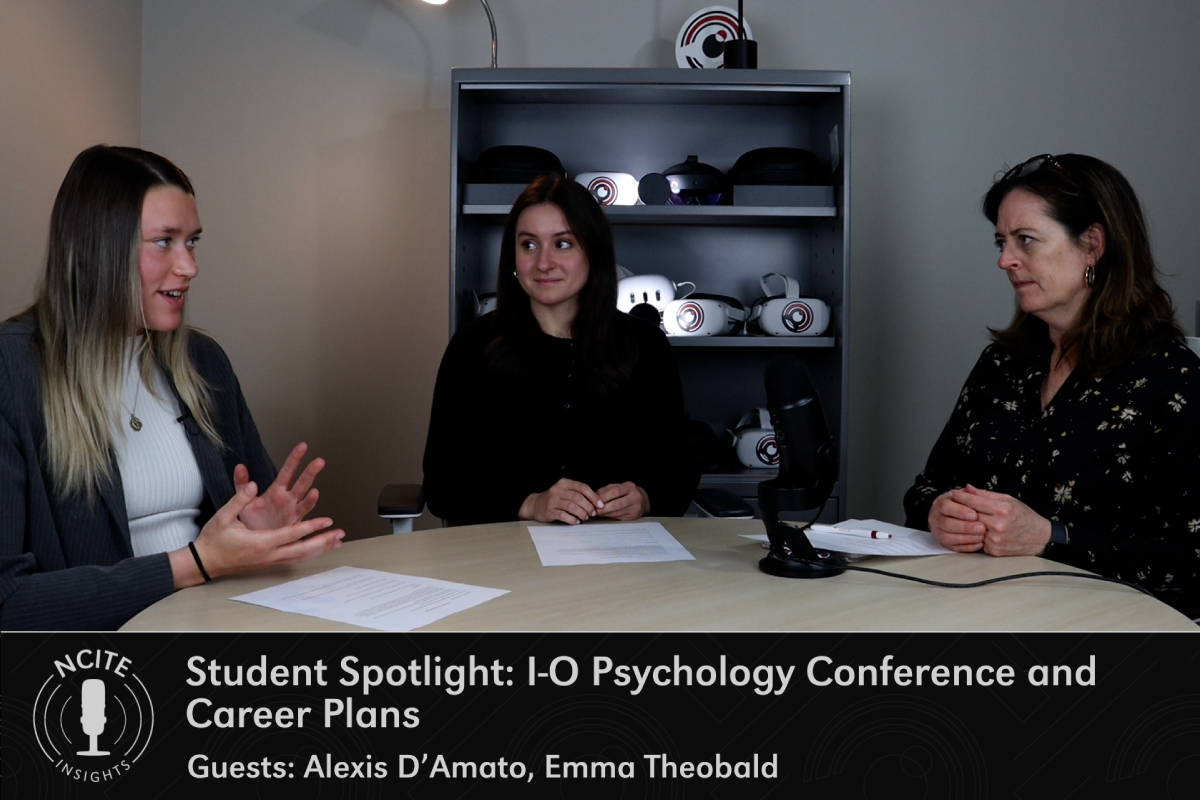

NCITE Insights No. 30 — Student Spotlight: I-O Psychology Conference and Career Plans

Erin sits down with Alexis D'Amato and Emma Theobald, two NCITE researchers and UNO graduate students in industrial and organizational psychology in the College of Arts and Sciences, to discuss their recent trip at the Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP) conference in Denver, CO.

RECAP: Protecting the Supply Chain with Jenni Hesterman

On March 27, NCITE hosted Jennifer Hesterman, Ed.D., for a presentation on securing the supply chain. Hesterman is retired Air Force colonel and a national expert on securing soft targets.

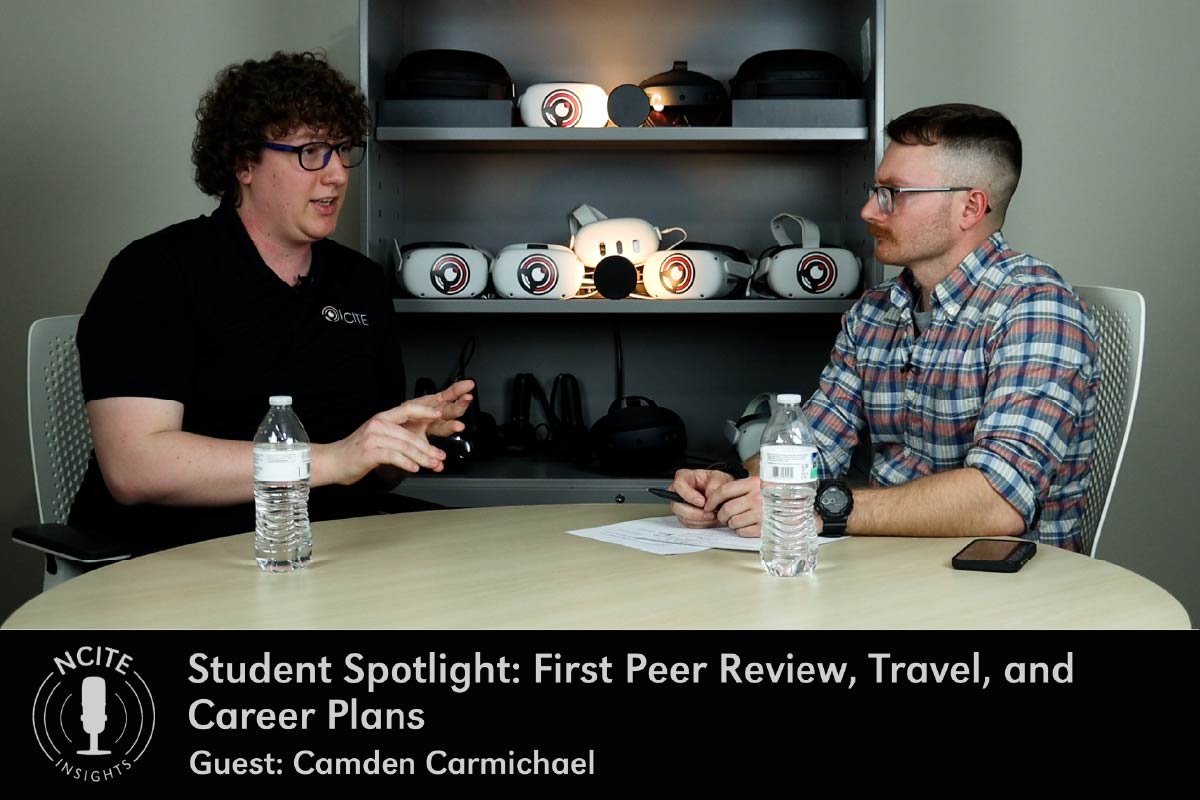

NCITE Insights – Student Spotlight: Camden Carmichael

On the latest episode of the podcast, Blake sits down with Camden Carmichael, an NCITE student researcher and undergraduate in the UNO School of Criminology and Criminal Justice. They discuss Carmichael's recent trip to the National Targeting Center in Washington, D.C., becoming a co-author on his first peer-reviewed paper, and his post-graduation plans.

NCITE Insights No. 27 – Terrorist Recruitment, Desired Skills, and AI

On the latest episode of the podcast, Erin sits down with NCITE researcher Evan Perkoski, Ph.D., to discuss his team's research on terrorist recruitment trends.

Extras

How NCITE and Duke Are Using War Games to Spark Interest in National Security

In an NCITE-funded project, researchers at Duke University taught a class that aimed to spark an interest in national security careers using war game simulations.

WEBINAR RECAP: Stopping Terrorism at the Border

On March 5, NCITE hosted a webinar with Jorge Comas, director of the Counter Network Division at U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) National Targeting Center, about efforts to keep terrorists from crossing U.S. borders.

The Hidden Cost of Security: A Short Guide to Understanding Vicarious Trauma

In a new booklet, NCITE researchers Joseph Young, Ph.D., and Daisy Muibu, Ph.D., illustrate the impact of exposure to violent material on the counterterrorism workforce and what can be done to address it.